Teaching Speech: Encouraging Good Learning Practices

David Hooperhooper[at]waseda.jp

Waseda University (Tokyo, Japan)

Introduction

Many university English programmes will include speech as either an integral part of the curriculum or, at the very least, an elective option. Teachers assigned to teach a speech class may be given guidelines regarding overall course objectives; however, the specific aims, content, methodology and assessment procedures often will be at the teacher’s discretion. Few teachers have specialized training or background in the area of public speaking and rhetoric. Consequently, many teachers, although making genuine attempts to include a strong oral component to their course, omit to cover some of the key elements that a designated speech course demands.The argument is proposed that audience participation and peer evaluation are important tools at the teacher’s disposal as a means of providing constant feedback and support to students studying both the theoretical and practical aspects of speech. A strategy is suggested for helping cope with larger classes, and consideration is given to some of the current ideas related to student learning research and theory.

What Is Speech?

Speech, used in this context, refers to public speaking and presentation; it is not merely a synonym for speaking, talking, conversation or debate. The area of speech has its own distinct vocabulary and terminology, and is concerned with public speaking and specifically identified types of speech and presentation.What Should an Introductory Speech Course Include?

A proposed speech course should include, in some form or another, the following topics:- The vocabulary of speech terminology.

- How to prepare a speech outline (with an appropriate introduction, body and conclusion).

- The key points of presentation, including the importance of eye contact, body movement and the voice.

- The roles of both the speaker and the audience.

- Identifying and categorizing different types of speech.

- How to judge and evaluate a speech.

Coping with Large Classes

In addition to time constraints, many teachers have a large number of students enrolled for a speech class. How can a teacher best utilize the time to ensure that all the students are participating constantly and are actively involved, whether as speakers themselves or as members of an audience? Requiring all members of the class to contribute to the evaluation process is one way to ensure that at no time is any student just a passive observer.Understanding the roles of both the speaker and the audience is one of the key elements of studying speech. Audience participation is about being able to identify and assess the style of speech, evaluating the content, judging the weak and strong points of delivery, and being capable of offering quality feedback to the speaker in the form of valid criticism.

A Practical Example

With a large class and only half a dozen students elected to actually make speeches on a given day, the class might be organized as follows:Divide the class into three equal groups. The first student presenting the speech will speak to the whole class who will act as the audience. At the end of the speech, one third of those students will be responsible for completing a student evaluation sheet. While that sheet is being filled in, another student can present his or her speech, but this time speaking to only two-thirds of the class. Again, at the completion of the speech, the students effectively rotate, so that at any one time, one third are completing and evaluating the previous speech, while two-thirds of the audience are engaged in the role of audience.

Peer Evaluation and the Student Evaluation Sheet

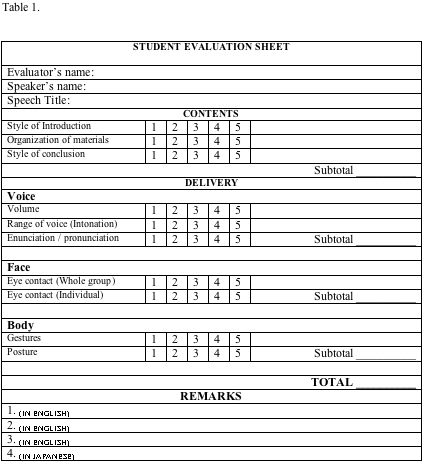

The student evaluation sheet is divided into three main sections: the contents, the delivery, and remarks. An example is given below: .

.For any given category, other students, based on what they have studied so far in the course, will have to make a judgment on a one (poor)-to-five (excellent)-point scale as to how well the speaker has performed. At the bottom of the sheet, the students are required to make four comments about the overall performance, three of which should be in English, and one of which can be in their native language. Students will need a lot of guidance initially to be able to make appropriate comments (particularly in English), and providing them with a list of examples for reference, is advisable. Such a list might include the following:

STRONG POINTS

- Good job. A well-organized speech.

- Well done. A well-prepared speech.

- Good delivery. You held your audience well.

- Interesting information. I learned something I didn’t know before.

- Very funny. I laughed.

- You were very enthusiastic about your subject.

- Good strong voice.

- Your intonation was very natural.

- Good, clear pronunciation.

- Eye contact was good. You looked at everybody.

WEAK POINTS

- Wait until everyone is listening before you start.

- Speak up! I couldn’t hear you.

- You sound like a robot. Put more expression in your voice.

- Slow down. It is not a race.

- Relax. Don’t fiddle with your (hair/clothes/paper…)

- Look at your audience, not the (floor/ceiling/teacher…)

- It’s O.K. to make a mistake, but say “Excuse me” in English, no in your native lanaguage.

- Your pronunciation is unclear, especially the sounds (r/l, s/th…)

- You should have practiced more.

- Don’t end your speech with “That’s all.”

Each student who has made a presentation will thus receive at the end of the class period not only at least ten completed evaluation sheets from other class members, but also one sheet completed by the teacher.

Why Is Peer Evaluation Important?

The value of peer evaluation lies not simply in the obvious practical advantage that students are constantly engaged in the teaching and learning process rather than mere passive observers. It is a valuable means of giving students direct feedback and providing a means of assessment that is directly related to the stated intentions of the course. It also helps to create a learning environment where the teacher does not assume all the responsibility, but facilitates and guides. The more intrinsic motivation to do well in front of peers is often in sharp contrast to the purely extrinsic motivation of “getting a good mark.”Aligning Assessment Procedures to Intended Course Outcomes

Regardless of the stated aims of an English speech course, many teachers feel that the improvement of student learning is the overriding concern. If we accept that our task, as teachers is to encourage our students to engage in the kinds of learning activities that will result in improved student learning, then it is essential that the assessment procedures that are adopted reflect those intended outcomes. Shuell (1986:429)) is absolutely correct when he points out that:It is helpful to remember that what the student does is actually more important in determining what is learned than what the teacher does.”Students, who see their final grade as being determined solely upon their showing up to class and subsequently reproducing the course content sufficiently accurately on a final exam, will engage in a type of learning and task processing that will have little long-term value. If the assessment procedure is an on-going, active process in which all students participate, and which is seen to be legitimate and valid, students are required to adopt a different approach in order to be successful.

Whether a teacher has a stated philosophy of education or not, the organization of his or her course will clearly reflect an underlying view. Taking what has been referred to in the literature (Cole, 1990; Marton, Dall’Alba, & Beaty, 1993) as a quantitative as opposed to a qualitative approach to learning, typically involves a final test based on the memorization of facts, or an assessment procedure that encourages a surface approach to learning—the very antithesis of that which most conscientious teachers would claim to support. It is now quite clear that the way in which tasks are processed will greatly affect the learning outcomes: surface processing leads to disjointed, bitty outcomes; deep processing results in well-structured outcomes (Biggs, 1979; Marton and Saljo, 1976; Trigwell and Prosser, 1991; Watkins, 1983).

Quantitative Versus Qualitative Approaches to Teaching and Learning

The quantitative outlook perceives learning as essentially the accumulation of knowledge—more bits of knowledge are internalized and capable of being accurately and speedily reproduced (at the time of assessment, at least). Assessment procedures typically involve reducing this knowledge to learned binary units (correct or incorrect) with an aggregate or total score compared against a final test score, which can be converted into a number and ultimately a grade. Multiple choice tests, and even essay-style tests which have a quantitative basis of marking, evaluate responses, not in terms of their intrinsic worth, but on the extent to which they correlate with a final test score. This kind of testing sends a clear message to the students that:There is no need to separate main ideas from detail; all are worth one point. And there is no need to assemble these ideas into a coherent summary or to integrate them with anything else because that is not required. (Lohman, 1993:19)Such teaching and assessment obviously encourages a surface approach to learning—an approach not necessarily espoused by the teacher, but plainly in evidence in the typical organization and structure of university teaching: large classes, expository teaching and final exams requiring accurate reproduction of lecture content.

In the qualitative outlook, however, learning is a cumulative process with new material being interpreted and absorbed into existing knowledge.

In the quantitative outlook assumptions are made about the nature and the acquisition of knowledge, that are untenable in the light of what is now known about human learning. (Biggs, 1994)The teacher’s role is not to transmit new knowledge; rather it is to help students construct understandings by adopting an approach to teaching that engages students in constructive as well as receptive learning activities. Biggs (1989) suggests that such kinds of activities should include:

- A positive motivational context, hopefully intrinsic but at least one involving a felt need-to-know and an aware emotional climate.

- A high degree of learner activity, both task-related and reflective.

- Interaction with others, both at the peer level with other students, and hierarchically, within “scaffolding” provided by an expert tutor.

- A well-structured knowledge base, that provides the longitude or depth for conceptual development and the breadth, for conceptual enrichment.

Applying Theory to Practice

There is always a danger of trying to directly apply theory to practice, especially when a lot of psychological-based theory and speculation is not derived from the context within which it is to be applied. Having said that, however, even those teachers who profess to have little interest in “theory” per se, and who rely exclusively on experience to judge what does or does not work in the classroom, will, inadvertently or intentionally, encourage their students to adopt a particular approach to learning.There may be some grounds for suggesting that teaching a speech class (or any kind of ESL class, for that matter) is a unique kind of learning experience. However, learning English at the university level should be more than just simple language acquisition. Any increased competency in the second language should be accompanied by a continual improvement and development of overall learning.

References

- Biggs J.B. (1979). Individual differences in study processes and the quality of learning outcomes. Higher Education, 8, 381-394.

- Biggs J.B. (1989). Approaches to the enhancement of tertiary teaching. Higher Education Research and Development, 8, 7-25.

- Biggs J.B. (1994). Learning outcomes: Competence or expertise. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Vocational Education Research, 2(1), 1-18.

- Cole, N.S. (1990). Conceptions of educational achievement. Educational Researcher, 19(3), 2-7.

- Lohman, D.F. (1993). Teaching and testing to develop fluid abilities. Educational Researcher, 22(7), 12-23.

- Marton, F., Dall’alba, G. & Beaty, E. (1993). Conceptions of learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 19, 277-300

- Marton, F. & Saljo, R. (1976). On qualitative differences in learning – 1: Outcome and process. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 4-11.

- Shuell, T.J. (1986). Cognitive conceptions of learning. Review of Educational Research, 56, 411-436.

- Trigwell, K. & Prosser, M. (1991). Relating approaches to study and quality of learning outcomes at the course level. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 265-275.

- Watkins, D.A. (1983). Depth of processing and the quality of learning outcomes. Instructional Science, 12, 49-58. Chapter 1: The research context.

The Internet TESL Journal, Vol. XI, No. 7, July 2005

http://iteslj.org/

http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Hooper-Speech/